From Satellites to Browsers: The 30-Year Evolution of Digital Pathology Viewers

Pathology’s march of progress

Digital pathology faced a paradox for decades: whole slide images are massive, but pathologists need to navigate them smoothly, zooming from the entire slide down to individual cells in seconds. The solution required technologies from satellite imaging, web mapping, video game graphics, genomics research, and cloud infrastructure to all converge at the right moment.

This story isn’t just about incremental improvements. Digital pathology viewers evolved through three completely different architectural paradigms, each enabled by specific technological breakthroughs. Understanding this evolution reveals why certain approaches dominated for years, why they eventually became obsolete, and why the transformation that happened in 2021-2022 wasn’t just an upgrade, but a fundamental shift to how medical imaging works.

An Unexpected Origin: Satellite Imaging Pioneers Pathology

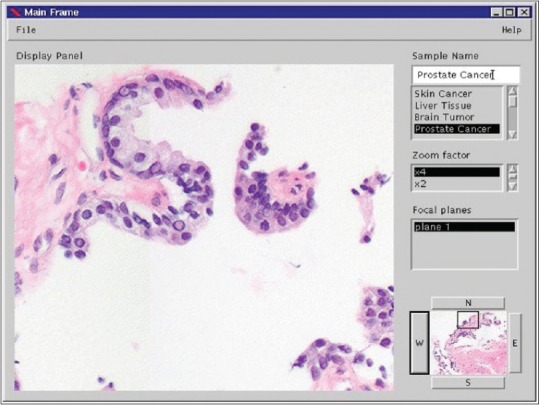

The foundational architecture for modern digital pathology viewers didn’t emerge from medical imaging at all. In 1996-1998, Joel Saltz’s research group at Johns Hopkins and the University of Maryland published the first whole-slide imaging viewer system by explicitly adapting technology from satellite imaging. AMIA 1997

Their “Virtual Microscope” implemented multi-resolution tile pyramids, spatial partitioning, and client-side caching—all borrowed from the Active Data Repository (ADR) system designed for map-reduce operations on satellite imagery. The team faced an interesting challenge: when they started this work in 1996, commercial whole-slide scanners didn’t exist yet. They created tiled images using photomicrograph platforms, establishing the tile-based pyramid architecture that would become universal.

Published in AMIA proceedings in 1997-1998, this work predated Google Maps by seven years. The core concepts were identical: organize gigapixel images as multi-resolution pyramids of 256×256 or 512×512 pixel tiles, cache aggressively, and prefetch adjacent regions. Every digital pathology viewer built since follows this pattern.

The architecture made intuitive sense: scanning a slide at 40× magnification produces images around 100,000×100,000 pixels. No computer in the late 1990s could handle that in memory. By organizing the image as a pyramid with multiple resolution levels, viewers only needed to load the specific tiles visible on screen at the current zoom level.

The Desktop Era: Power and Isolation

Commercial whole-slide scanners arrived shortly after the Virtual Microscope research. The first being the BLISS (Bacus Laboratories Inc., Slide Scanner) system, designed in 1994. Aperio launched its ScanScope system in 2000, introducing the proprietary SVS format. Other vendors quickly followed: Hamamatsu’s NDPI, Leica’s SCN, Ventana’s BIF, and 3DHistech’s MRXS. Each implemented pyramidal structures differently, but all faced the same fundamental challenge: delivering gigapixel images to workstations.

The early 2000s desktop era was defined by three constraints: file size limits, proprietary vendor lock-in, and isolated workstations.

The TIFF format specification used 32-bit offsets, creating a hard 4GB file size limit that whole-slide images increasingly exceeded. This drove the development of BigTIFF between 2004-2007. By changing header bytes from 42 to 43, BigTIFF switched to 64-bit offsets, theoretically supporting files up to 18 exabytes. The stable release arrived in December 2011 (LibTIFF 4.0), finally removing the constraint that had forced awkward multi-file workarounds.

Desktop applications like Aperio ImageScope (2000), Definiens Developer XD (2011), and HALO (2012) provided powerful analysis capabilities but required local installation on each workstation.

The proprietary formats created severe vendor lock-in: SVS files needed Aperio’s libraries, NDPI required Hamamatsu’s SDK, and cross-vendor interoperability was essentially impossible. If you bought Scanner A, you were locked into Vendor A’s software ecosystem. This couldn’t scale to support the distributed, collaborative workflows that pathology departments increasingly needed.

The Google Maps Moment: Expectations Transform

February 8, 2005 marked a pivotal moment for all large-image viewing when Google Maps launched publicly. The “slippy map” interface used AJAX to deliver 256×256 pixel tiles asynchronously without page refreshes. The pyramid structure with multiple zoom levels proved that gigapixel-scale datasets could be navigated smoothly in web browsers—eliminating the assumption that such interfaces required desktop applications.

The influence on digital pathology was immediate and explicit. Technical papers and product descriptions openly stated goals like “provide a Google Maps-like experience for pathology slides.” The architecture was directly applicable: pathology slides have the same multi-resolution pyramid structure, benefit from the same tile-based streaming (load only visible regions), and need identical user interactions (smooth panning, zooming, rotation).

Google Maps didn’t just inspire pathology—it changed user expectations. Pathologists who could smoothly navigate Google Earth on their home computers found desktop pathology applications cumbersome. Why did viewing a slide require specialized workstations when mapping the entire planet worked in a browser?

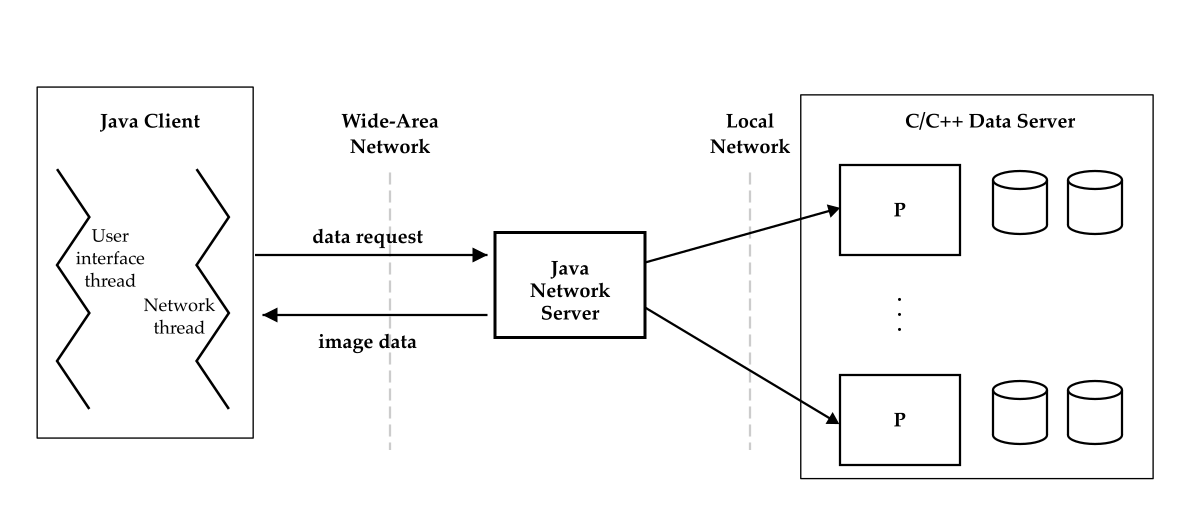

OpenSlide emerged around 2010-2013 as the critical bridge technology. This vendor-neutral C library (with Python and Java bindings) provided a unified interface to read proprietary WSI formats from Aperio, Hamamatsu, Leica, and others. Published in the Journal of Pathology Informatics in 2013 by Goode et al. from Carnegie Mellon and Johns Hopkins, OpenSlide became the middleware layer that broke vendor lock-in, enabling third-party viewers to support multiple scanner formats.

OpenSeadragon, released around 2010-2012 as an open-source variant of Microsoft’s Seadragon technology, became the de facto JavaScript library for viewing high-resolution images in browsers. Supporting Deep Zoom Images (DZI) format with a plugin architecture, OpenSeadragon provided the client-side rendering framework that numerous pathology viewers adopted.

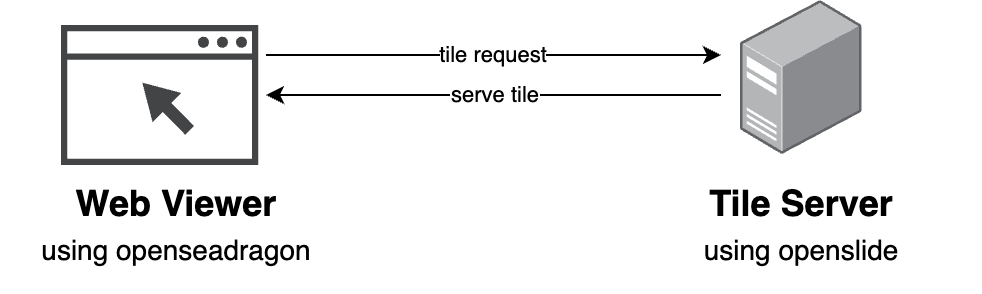

By the mid-2010s, the pattern was established: OpenSlide on the server side to read proprietary formats, a tile server to extract and serve tiles on-demand, and OpenSeadragon in the browser to display them.

The WebGL Bottleneck: 2011-2014 Limbo Period

The Khronos Group released the WebGL 1.0 specification in March 2011, bringing OpenGL ES 2.0 capabilities to web browsers and theoretically enabling GPU-accelerated rendering without plugins. Chrome 9 (February 2011) and Firefox 4.0 (March 22, 2011) immediately implemented support.

September 2014 marks the true inflection point: WebGL 1.0 reached greater than 80% browser support, making it production-ready. This 3.5-year gap from specification release to practical availability illustrates why web-based pathology viewers lagged behind theoretical possibilities.

Early WebGL implementations also suffered from texture size constraints (typically 4096×4096 maximum, while whole-slide images exceeded 100,000×100,000 pixels), memory management issues (browser limits of 2-4GB), and cross-origin restrictions that complicated deployment architectures.

During this period, commercial vendors transitioned cautiously to web viewing with server-side rendering approaches. Aperio WebScope appeared in the early-mid 2010s, followed by Aperio WebViewer in 2015, providing browser-based viewing but still relying on server infrastructure to generate and serve tiles.

Network and Cloud Infrastructure Mature

Amazon Web Services launched S3 on March 14, 2006, introducing object storage with HTTP/HTTPS access and range request support from day one. But cloud storage wasn’t immediately viable for medical imaging.

In 2006, average global bandwidth was only 2-5 Mbps, and HIPAA compliance frameworks didn’t yet cover cloud storage. The 2013 announcement of HIPAA-eligible AWS services (including S3) marked the regulatory turning point, while network speeds reached 20-30 Mbps average in the US—the threshold where tile-based streaming became practical for clinical use.

Hospital network infrastructure evolved in parallel. The 2010 FCC Healthcare Broadband Report documented that 92% of Indian Health Service sites had ≤1.5 Mbps connections and established that large hospitals required 1 Gbps minimum bandwidth. By 2005-2010, major hospitals completed 1 Gbps campus rollouts. By 2015, 1 Gbps to desktops became standard with 10 Gbps backbones.

This infrastructure investment was critical: whole-slide images averaging 2.5 GB required 50-100 Mbps for smooth tile-based streaming. 100 Mbps became the minimum standard for digital pathology workstations by the late 2010s.

Cloud storage pricing fell dramatically. S3 Standard storage dropped from $0.15/GB/month in 2006 to $0.023/GB/month by 2017—an 85% reduction. Archive tiers reached $0.001-0.004/GB/month, making petabyte-scale storage affordable.

However, data transfer costs ($0.09-0.12/GB outbound) often exceeded storage costs for frequently accessed images, creating architectural incentives to minimize data movement and favor client-side processing.

The 2017 Convergence: Everything Matures Simultaneously

2017 represents the crucial convergence year when multiple technologies simultaneously reached production maturity.

WebGL 2.0 shipped in Firefox 51 and Chrome 56/57 in January-March 2017, adding transform feedback, instanced rendering, multiple render targets, 3D textures, and improved texture formats based on OpenGL ES 3.0. More importantly, the performance and reliability had matured—memory management improved, garbage collection pauses dropped to 10-50ms (from 100-500ms in 2010), and GPU driver issues were largely resolved.

WebAssembly’s MVP specification reached consensus in March 2017, with Firefox 52 (March 7, 2017) and Chrome 57 (March 9, 2017) providing immediate support, followed by Safari 11 (September 19, 2017) and Edge (October 31, 2017). By Q4 2017, all major browsers supported WebAssembly, enabling near-native performance (typically 1.5-2× slower than native C++) for computational tasks.

This was transformative for medical imaging: complex image codecs like JPEG 2000, OpenJPEG, and libtiff could be compiled to WebAssembly and run efficiently in browsers, achieving 5-10× faster decoding than JavaScript implementations. The ability to handle full-bit-depth data (int8/16/32, uint8/16/32, float32/64) directly in WebAssembly closed the performance gap with desktop applications.

JavaScript engine performance improvements compounded these gains. Chrome’s V8 introduced the Ignition interpreter + TurboFan compiler pipeline in 2017, replacing the older Crankshaft compiler. This delivered 20-30% real-world performance improvements and reduced memory usage. Firefox Quantum (November 2017) brought parallel CSS processing and GPU-accelerated rendering.

Across benchmarks from 2008-2017, JavaScript performance improved 100-1000× depending on workload, with overall improvements around 10× for typical applications.

The combination of browser capabilities, codec performance, and network speeds made 2017-2018 the inflection point when sophisticated web-based viewers became technically and economically viable at clinical scale. But one piece was still missing: a cloud-native image format.

Format Evolution: From Monolithic Files to Cloud-Native Storage

While browsers and networks matured, image formats remained a constraint. Proprietary formats like SVS, NDPI, SCN, and BIF were monolithic files—single large files with internal pyramid structures. Even with HTTP range requests (standardized in RFC 7233, June 2014), accessing specific tiles required seeking to byte offsets within multi-gigabyte files.

Server-side infrastructure had to read these files, parse TIFF directory structures, locate tile offsets, extract compressed data, and serve it—creating unavoidable latency and scaling limitations.

The OME-TIFF standard from the Open Microscopy Environment consortium embedded OME-XML metadata in TIFF ImageDescription tags, enabling richer metadata and multi-file datasets with UUID tracking. The 2019-2020 addition of SubIFD support (OME-TIFF version 6.0) enabled multi-resolution pyramids with image stacks in standardized structures. But OME-TIFF remained a monolithic file format, still requiring server-side tile extraction.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source: genomics research.

Zarr was created by Alistair Miles at the University of Oxford around 2015, designed for massively parallel array analytics in genomics. Zarr stored chunked, compressed N-dimensional arrays with metadata in JSON files and binary data in individually referenceable chunk files. The architecture was storage-agnostic and enabled parallel reads and writes without locking.

The bioimaging community recognized that Zarr’s architecture solved the cloud-native viewing problem. Instead of a monolithic file with internal organization, each chunk could be a separate object with a predictable URL pattern. A slide’s pyramid might contain thousands of chunks, each directly accessible via HTTP GET requests to specific URLs like 0/0/0/0 for pyramid level/channel/y/x.

Standard web servers or object storage (S3, Google Cloud Storage, Azure Blob, MinIO) could serve these chunks without any processing.

OME-NGFF (Next-Generation File Format) 0.1 was publicly specified in November 2020, adapting Zarr for microscopy with multiscale image pyramids, label images, and 5-dimensional arrays. The formal publication in Nature Methods appeared on November 29, 2021 (online August 2021), authored by Josh Moore and Chris Allan from Glencoe Software with the OME team.

OME-NGFF wasn’t just another format but an architectural transformation. Version 0.2 (early 2021) changed the dimension separator from “.” to “/” based on benchmarks revealing 10× performance improvements for remote access with cloud storage. This seemingly minor change had major implications: cloud object storage performs better with hierarchical paths than with filenames containing many dots.

By late 2021, OME-NGFF had reached version 0.4 with refined axis transformations and JSON Schema validation. The specification was stable, implementations existed, and conversion tools like bioformats2raw could transform any of the 150+ proprietary formats (via Bio-Formats) into OME-NGFF.

![Random sampling of 100 chunks from synthetically generated, five-dimensional images measures access times for three different formats on the same file system (green), over HTTP using the nginx web server (orange) and using Amazon’s proprietary S3 object storage protocol (blue) [Nature Methods 2021] Random sampling of 100 chunks from synthetically generated, five-dimensional images measures access times for three different formats on the same file system (green), over HTTP using the nginx web server (orange) and using Amazon’s proprietary S3 object storage protocol (blue)](/images/blog/ome-ngff-performance.webp)

The Pure Client-Side Breakthrough: May 2022

On May 11, 2022, Trevor Manz, Ilan Gold, and colleagues from Harvard Medical School, Vanderbilt University, and Indiana University published Viv in Nature Methods. Viv demonstrated pure client-side rendering of biomedical images entirely in the browser using WebGL, with zero server-side processing required beyond static file hosting.

Viv’s architecture exploited the convergence of technologies that had matured over the preceding five years. Built on Uber’s deck.gl framework, Viv implemented data loading modules for OME-TIFF (with HTTP range request support) and OME-NGFF/Zarr (with direct chunk access).

The rendering pipeline operated entirely on the GPU: custom WebGL shaders performed multichannel imaging operations, real-time color mapping, opacity adjustments, and channel visibility toggles—all computed locally without server communication. The implementation supported full-bit-depth data (int8/16/32, uint8/16/32, float32/64) and included components like PictureInPictureViewer, SideBySideViewer, and VolumeViewer with raycasting for 3D visualization.

The chunk-based storage structure in OME-NGFF mapped perfectly to WebGL’s texture loading:

- HTTP requests fetched specific image chunks directly from storage

- WebGL shaders processed the full-bit-depth data

- GPU rendering produced the final composited image

User interactions like brightness adjustments or channel selection were instant—computed by the GPU in milliseconds rather than requiring server roundtrips.

The architectural transformation was profound:

Traditional server-side flow:

| |

Viv’s client-side flow:

| |

The entire tile server layer was eliminated.

Commercial Versus Open Source: A Symbiotic Evolution

The evolution of digital pathology viewers reflects continuous interplay between commercial and open-source development, with each approach enabling and accelerating the other rather than competing independently.

Commercial vendors led hardware integration (2000-2010): Aperio, Hamamatsu, Leica, and Philips developed integrated scanner-software systems with proprietary formats optimized for their hardware. The commercial investment in scanner technology and FDA regulatory pathways created the market foundation. But proprietary formats created vendor lock-in and interoperability barriers.

Open source broke vendor lock-in (2010-2013): OpenSlide provided vendor-neutral format reading, enabling third-party viewers to support multiple scanner types. This forced commercial vendors to either open their formats or risk losing customers to platforms offering broader compatibility.

Commercial cloud platforms established enterprise requirements (2014-2019): Proscia, Paige.AI, PathAI, and Philips PathologyHub defined what enterprise-scale digital pathology platforms needed: LIS integration, multi-user collaboration, AI algorithm deployment, regulatory compliance, and clinical-grade security. These commercial implementations validated cloud-based architectures and established pricing models.

Open source demonstrated pure client-side viability (2020-2022): OME-NGFF specification development (led by academic and open-source communities) and Viv implementation (Harvard Medical School, NIH HuBMAP Consortium) proved that server-side rendering was no longer necessary. This eliminated the cost barrier of maintaining server infrastructure, enabling smaller institutions and research groups to deploy sophisticated viewing capabilities.

Commercial vendors adopted open standards (2022-present): The success of OME-NGFF and demonstrated viability of client-side rendering pushed commercial vendors toward standards adoption. Glencoe Software (commercial company behind much OME development) integrated OME-NGFF support across products. Major vendors began supporting or planning support for cloud-native formats alongside proprietary options.

The pattern repeats: commercial development addresses enterprise needs and provides resources for complex integration, while open-source efforts solve interoperability problems and demonstrate new architectural possibilities that become industry standards. Neither approach could have achieved the 2022 breakthrough independently. Commercial investment funded the underlying technology development (scanners, formats, regulatory work), while open-source collaboration solved the standardization and accessibility challenges that enabled the final architectural leap.

So where’s cytario in this story?

The cytario® platform is built on client-side rendering from day one. Utilizing the Viv library for direct browser access to OME-TIFF and OME-NGFF images in object storage. What’s new is the combination with enterprise requirements such as secure access, identity management incl. SSO and SAML, data transfer and open interfaces to connect different tools.

Because it is about time that we move on from virtual microscopes to computational pathology and vendor lock-in and proprietary software are in the way.

Interested in learning how cloud-native architecture can simplify your digital pathology infrastructure? Let’s talk about your specific requirements.

Further Resources

Foundational Papers

- Ferreira et al., AMIA 1997 – Virtual Microscope (first WSI system)

- Goode et al., JPI 2013 – OpenSlide (vendor-neutral infrastructure)

- Bankhead et al., Scientific Reports 2017 – QuPath

- Pantanowitz et al., JPI 2018 – Twenty Years of Digital Pathology review

Cloud-Native Formats and Rendering

- Moore et al., Nature Methods 2021 – OME-NGFF introduction

- Manz et al., Nature Methods 2022 – Viv client-side rendering

- Moore et al., Histochemistry 2023 – OME-Zarr comprehensive overview

Standards and Specifications

- DICOM Supplement 145 – WSI standard (2010)

- WebGL Specification – Khronos Group

- OME-NGFF Specification – Current version

- Zarr Format – Technical documentation

Tools and Implementations

- Viv on GitHub – Client-side rendering library

- QuPath – Open-source analysis platform

- bioformats2raw – Format conversion